On A Wing and a Prey-er

The California Raptor Center celebrates a half-century of rescuing and rehabilitating raptors.

Light illuminates the brilliant white head of a bald eagle as it spreads its chocolate-brown wings and beats them against the air. The raptor — on the brink of death only months before after being hit by a car — lifts into the sky. This majestic moment of success was made possible through hours of painstaking rehabilitation and care provided by staff and a dedicated team of volunteers at the UC Davis California Raptor Center.

Celebrating its 50th anniversary this year, the school’s center — commonly known as the CRC or raptor center — has been preserving, protecting and promoting the health of all raptor species through rehabilitation, education and research since 1972. The center has saved thousands of birds of prey — including eagles, hawks, owls, falcons and vultures — while enlightening the community through its educational programs. The center’s team takes in between 100 to 300 sick, injured and orphaned birds each year for rehabilitation and treatment. It also makes a national impact on avian research.

Taking Flight

The center was founded when graduate student Alida Morzenti, and undergraduate students Mark Fenn and Ole Torgerson (who also happened to be falconers), approached avian sciences faculty member Dr. Frank Ogasawara and pitched the idea of starting a center dedicated to raptor rehabilitation. UC Davis was a prime location due to the migratory pattern of several species through the area, especially the Swainson’s hawk.

In fact, the first bird to arrive at the center’s original location near the University Airport was an orphaned Swainson’s hawk. (In homage, the center’s current logo features an illustration of that species.) After quickly outgrowing that location, the center moved to its present location off Old Davis Road.

In 1980, the center became part of the School of Veterinary Medicine. This new partnership meant sick and injured birds of prey could receive advanced medical care with veterinary specialists in many fields. It is also when Dr. Murray Fowler, widely recognized as the father of zoological medicine, became director of the center and Terry Schulz became its supervisor. Fowler and Schulz saw the center as providing an excellent educational opportunity for veterinary students who became the center’s primary volunteer staff, learning how to handle, treat and rehabilitate sick and injured raptors.

After Fowler’s retirement, Dr. Dale Brooks took over as center director in 1991. Brooks had a vision of expanding the facilities and educational mission. In 1992, Jo Cowen was appointed as volunteer head of education programs and the center opened to the public six days a week. Both of these events provided increased learning opportunities and engagement with the public.

Under Brooks’ leadership, the center also added a separate clinic and quarantine area, an office and classroom facility, new display cages for permanent resident birds, a museum and (much to the volunteer staff’s excitement) a permanent, on-site bathroom. The museum, which exists to this day, is an interactive, one-room building that includes taxidermied animals, touch-screen video players that explain the rehabilitation process, games for kids, and many interpretive displays.

“Dr. Brooks was not a raptor guy at all, but there was no one else who was willing to step up and manage the center,” said Bret Stedman, who served nearly 40 years of combined service as a volunteer and former director of operations. “The center exists today largely because of him.”

In 1998, Dr. Bill Ferrier was appointed operations director and Dr. Lisa Tell as medical director. Ferrier, a falconer in his spare time, also oversaw the Center for Laboratory Animal Science which meant used cages that were no longer needed could be retrofitted for birds and donated to the center. This made it possible for the center to accommodate more birds needing rehabilitation in larger spaces.

The center’s current director, Dr. Michelle Hawkins, started as medical director in 2005, taking over for Tell. In 2013, after Ferrier’s retirement, Hawkins was appointed as the center’s director in addition to being a full-time faculty member in the school.

Under Hawkins’ leadership, the center has partnered with the school’s One Health Institute to provide administrative and leadership support. She has also created a strategic plan and helped secure much-needed funding, including a major grant from the McBeth Foundation to build a new, zoo-quality exhibit for the center’s resident turkey vultures.

“Serving as director is definitely a labor of love, no doubt,” Hawkins said. “But it’s also a real honor to take care of patients who don’t have human support systems. To be able to take wild raptors from sickness and injury to health is very special.”

Valued Volunteers

The center has always relied heavily on a crew of dedicated volunteers, including veterinary, undergraduate and graduate students, and community members. Many of those volunteers go on to have impactful careers in wildlife management and the environment, such as Cicely Muldoon ’88, Yosemite National Park’s superintendent.

"My time at the center — starting in my first year of undergraduate studies — led me directly to what became my life’s work in the national parks,” Muldoon said. “The lesson I learned there is with me to this day: find meaningful work that taps your passions, contributes to society, and works for the good of the planet.”

Other volunteers end up staying for decades. Stedman, for example, began volunteering as an undergraduate in 1982 before being appointed director of operations 12 years later. In this role he not only trained all volunteers how to care for the birds, but he also taught classes on raptor rehabilitation to UC Davis students. He served in this role for 25 years before retiring in 2021.

The center’s current interim operations director, Julie Cotton, MS ’14, started as a volunteer when she was a graduate student. In 2017, she was hired as volunteer and outreach coordinator and, after Stedman’s retirement, Cotton was promoted to manage the day-to-day operations.

“Here we can directly see the difference we are making in the lives of the animals, but I also like that it is a public service to the community,” Cotton said.

Educational and Research Mission

The center is currently home to 35-plus permanent residents who cannot be released into the wild due to permanent damage from injury or being malimprinted on members of the public when young. Each of the resident raptors have names, stories and personality traits that are well known to the center’s staff, volunteers and frequent public visitors. Many of these “Educational Ambassadors” are on display for members of the public to visit. Prior to the pandemic, the center’s education team would host on-site and off-site presentations to school classes and other groups. Altogether, the center has touched the lives of about 10,000 people a year.

“We have visitors who say, ‘I came here on a field trip when I was in the third grade,’ and now they are bringing their kids to come visit,” Cotton said. “The fact that people come here generation after generation is amazing.”

The center’s Educational Ambassadors also provide opportunities for veterinarians to research infectious diseases, advance medical care, and collect biological data — allowing the center to be on the forefront of avian research. For example, in a recently published PLOS One study, Hawkins and colleagues documented the prevalence of a newly identified Chlamydial organism, Chlamydia buteonis, in raptors admitted to five wildlife rehabilitation centers in the state over a one-year period.

Flying Toward the Future

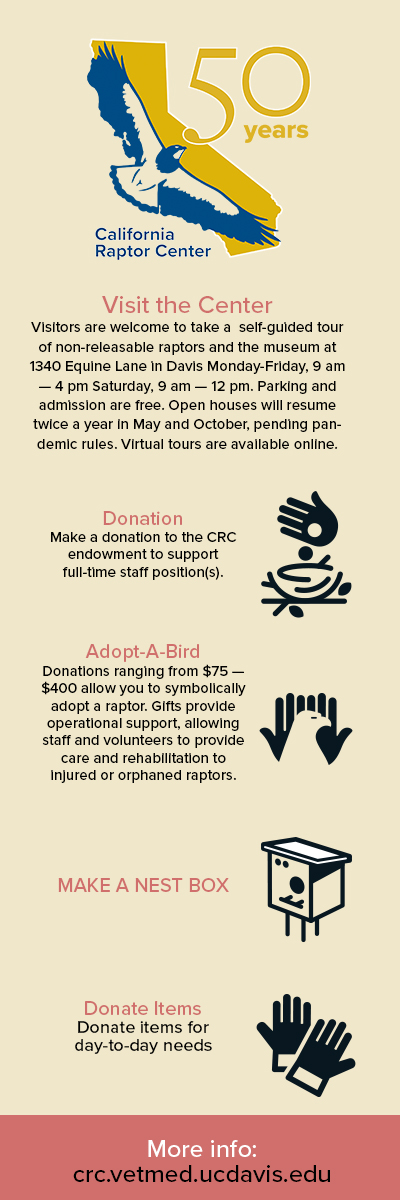

Philanthropy has always played a large role in the center’s operation. The majority of it came through two open houses it hosted each year and its educational presentations. However, the COVID-19 pandemic cancelled many of these events, leaving a large void in the center’s budget. In addition, the school has needed to cut its financial support. The center has increased its fundraising efforts seeking everything from in-kind donations of Dawn dish soap and trash bags, to adopt-a-bird opportunities, grants and major gifts. Still more is needed.

“We provide a level of care that I’m not sure any other center in the U.S. can provide,” said Hawkins. “We hope that we can grow our program to be sustainable so that we can accept more patients.”

While the center never turns down a raptor brought in by the public, Cotton added, sometimes they have to be conservative with treatment plans and work within limits of their space and staffing. In some cases, they may need to transfer birds elsewhere.

The center has evolved over time and will continue to do so. Those who have seen it grow over the years continue to support its mission passionately. Hawkins’ plans for the raptor center include updating and/or repairing some of the rehab facilities, improving the grounds, becoming more involved with state and federal governments on endangered species, and growing the center’s endowment to fully fund staff position(s) in perpetuity.

“The strength of this place has always been the dedication of great people, the quality of the work being done, the positive experience that visitors have, and a lot of great effort to help birds that otherwise wouldn’t survive,” Stedman said.