Honoring our Past, Embracing our Future

As the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine celebrates its 75th anniversary this year, we take a look back at the history that provided our foundation for leading veterinary medicine into the future.

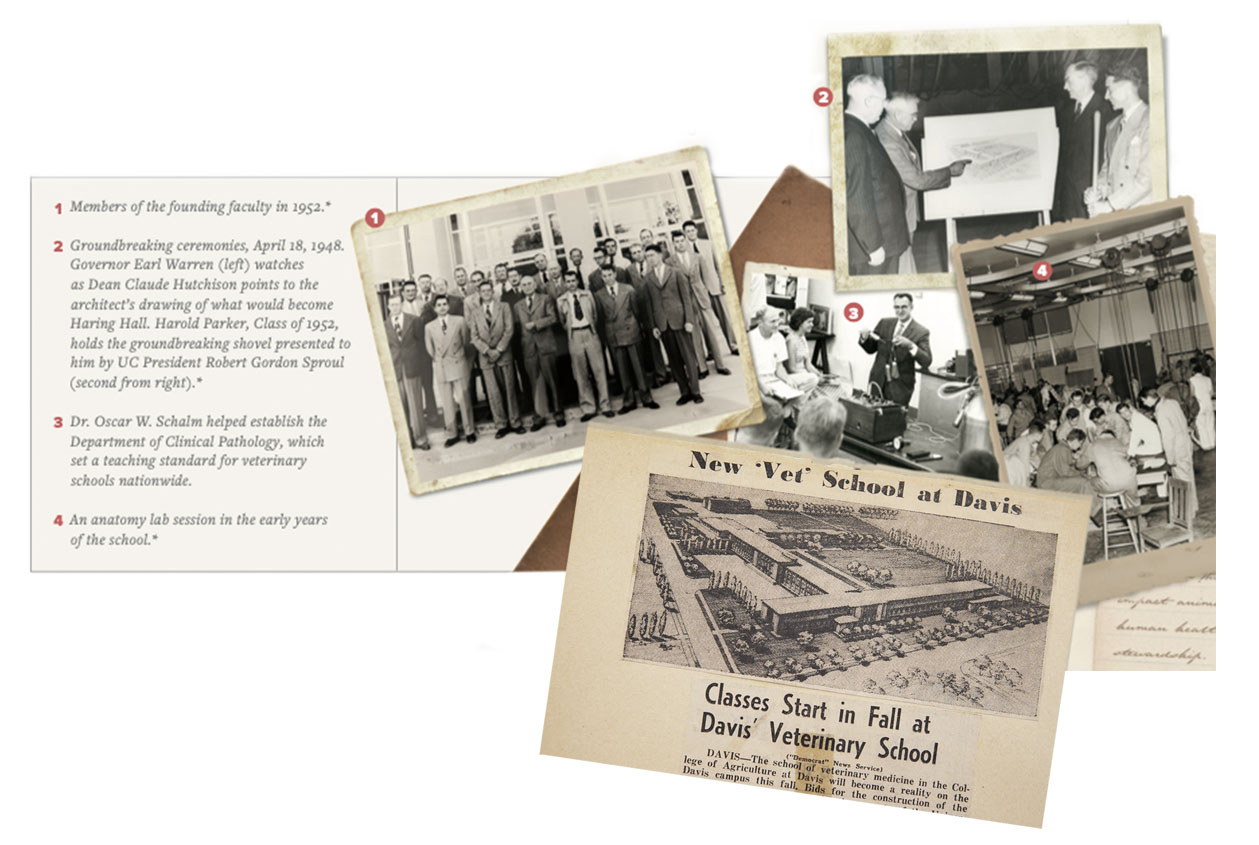

While we may be celebrating three quarters of a century, the genesis of the UC Davis veterinary school goes back much farther. Before the first class of 42 DVM students launched into studies in the fall of 1948, there was a failed University of California (UC) veterinary college in San Francisco; several decades of fighting for legislative support; the intervention of World War II; and the tireless energy of R. Vince Garrod, a prune and apricot grower from Saratoga, who pushed for the school to eventually be established.

The UC first organized a College of Veterinary Medicine in 1894 on the San Francisco campus. A total of ten students graduated before it closed in 1899 due to a lack of financial support and

low enrollment. At the time, most other veterinary colleges in the nation required only an elementary education while the UC required a high school diploma or the equivalent. In addition, there was competition from a privately supported San Francisco Veterinary College, specializing in equine health to care for horses needed for transportation.

Responding to a growing need for veterinary care in the state, UC Berkeley’s College of Agriculture established a Division of Veterinary Science in 1901

where research veterinarians began to investigate important diseases of livestock and poultry. As the UC Davis campus grew, some of the research activities were conducted here. Those activities became foundational to the future work of faculty and staff at the school.

Dr. Clarence M. Haring, a veterinary science professor and director of the UC Agricultural Experiment Station, sought to bring a DVM program to the Davis campus and first presented information on annual budgeting and building costs to the UC administration in 1920. That initial effort failed and by 1938, the American Veterinary Medical Association and the California Veterinary Medical Association cited an urgent need for veterinary training in the growing state. That same year, the California Farm Bureau passed a resolution at their annual meeting to “lend our influence toward the establishment of a College of Veterinary Science at the University of California.”

The case for a California-based veterinary school came before the State Board of Agriculture where Garrod was a member. As a leader in several other civic and business organizations, he became passionate in advocating for the school by gathering facts and information to present to the Legislature, the Governor, livestock organizations, Chambers of Commerce and the press.

He documented the needs of animal industries, the difficulty in finding veterinarians, and the role of veterinary medicine in protecting the public health.

News releases from the State Department of Agriculture on animal diseases bolstered those justifications. Those diseases included: a severe 1940 outbreak of equine encephalomyelitis; a screw- worm infestation in livestock; the growing concern over brucellosis in cattle; and an outbreak of dourine among horses in Arizona, California and Nevada with resulting quarantines and testing programs. All received widespread newspaper coverage and provided examples that emphasized to legislators and the public the need for greater competence in veterinary medicine.

World War II derailed the efforts to establish the veterinary school at Davis for a few years before a legislative bill finally passed in 1946 authorizing the school. Garrod summarized the steps it had taken to reach that place in a document that opened with this: “In the future, when California’s College of Veterinary Medicine is recognized as the leading institution of its kind in the world, and when the valuable contribution of its graduates to the general welfare will cause speculation as to why this great center of learning was not started long ago, no doubt, there will be need for a record of how the college was created, why it was created, when it was created and what was expected of it in the beginning.”

Breaking New Ground

Haring put off retiring for one year (after 43 years of service to the university) to act as the inaugural Dean of the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine from 1947–48, helping to develop a curriculum that “should be second to none.” He believed that the best teaching would be done by faculty members whose minds were challenged in demanding research laboratories. He guided a curriculum committee that recommended a Bachelor of Science degree in Agriculture be given at the end of the first two years of the veterinary curriculum; the last two years leading to the DVM degree would be placed under a Graduate Council.

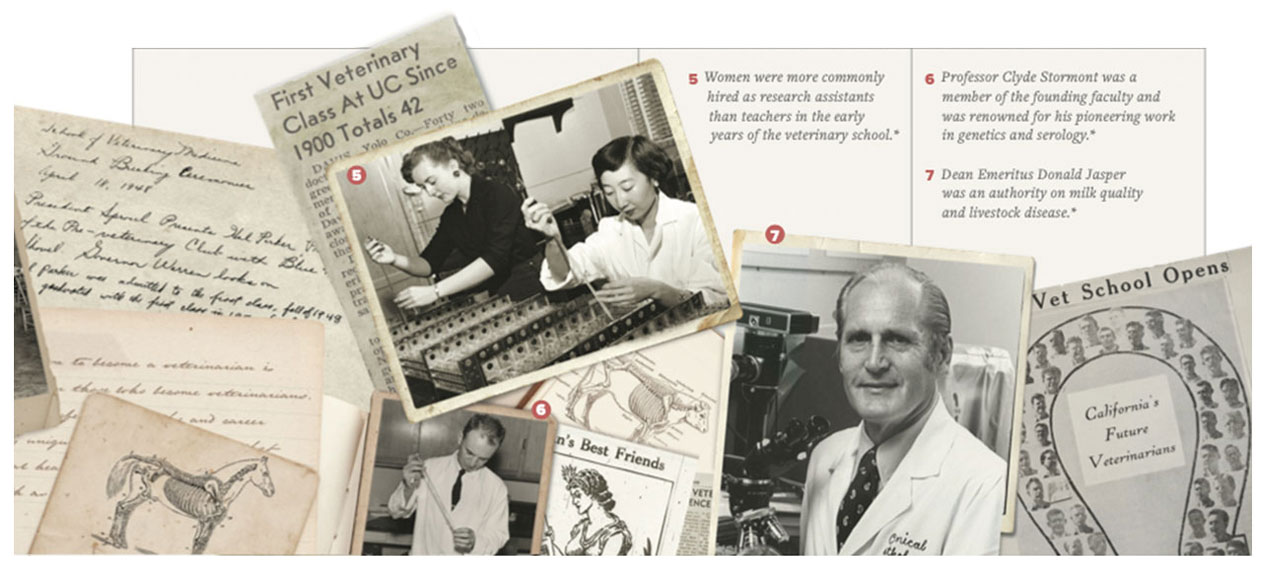

When the first class of 42 men (mostly WWII veterans) began courses in the fall of 1948, most of them studied livestock medicine to help control disease outbreaks and protect public health. The curriculum had been designed with key ideas and innovations, the most important being:

-

An emphasis on functional anatomy where several species were dissected simultaneously with reference to physiology, pathology and clinical practice.

-

A connection between basic laboratory sciences and applied veterinary medicine by establishing a Department of Clinical Pathology. Led by Dr. Oscar W. Schalm, this department became renowned for its leadership in hematology, mastitis and clinical biochemistry, and set a standard for teaching in other schools.

- The integration of traditional disciplines—for example, discussing normal cells and organs followed by discussion of abnormal or pathological.

While some of these initial ideas remain, curriculum committees throughout the past 75 years have constantly engaged to improve and revise coursework to provide the strongest foundation possible for the school’s DVM graduates.

Even after getting the legislative green light to establish the first professional school at UC Davis, planning the buildings and financing them remained a hurdle.

It was soon clear that the initial $500,000 provided by the state would be insufficient. As planning moved forward, material and labor costs increased drastically, bringing about discussions of a reduced program and building plans. To his credit, Haring refused to let the university back out of its pledge to build a first-class school.

Although a portion of the initial plans had to be scratched, the main building went forward with careful attention to construction appropriate for a medical and research facility. Rain moved the groundbreaking ceremonies indoors on April 18, 1948 to the Recreation Hall on the Davis campus. The project as eventually completed was designed to provide for 40 students per class, and contained 92,289 square feet with

an additional 10,000 square feet for clinic hospitals and an ambulatory clinic garage at a total cost of $4.5 million. It was dedicated on March 20, 1950 as the Veterinary Science Building, but soon after Haring’s death in July of 1951, the building was renamed Haring Hall.

At the time, many thought the building was too large. As Dean Emeritus Donald Jasper included in his recounting of the school’s history: “No one anticipated that within ten years the needs of veterinary medicine would have outgrown these marvelous quarters.”

Instruction began in the fall of 1948, before the school had its own facilities. That first year of classes, only two courses were required: a 9-unit course in anatomy in the fall and a 10-unit course in microbiology

in the spring. Makeshift laboratories in the Animal Science building worked reasonably well, although they proved quite crowded for anatomy. The following year introduced histology/pathology, pharmacology and parasitology.

Dr. George H. Hart took on the role of dean in 1948 and served for the following six years. Prominent in livestock and veterinary circles, Hart brought a strong reputation in the field of animal disease.

Under his tenure, the school established areas of responsibility that were informally referred to as “departments.” While those areas have changed and been refined over the years, the school still relies on six academic departments, each with a unique mission for propelling veterinary medicine forward. (See cover feature in Synergy’s Fall 2022 issue.)

An Executive Committee was formed to assure that members of the school had a voice in its governance. A Dean’s Advisory and Budget Committee was also established to deal with matters of interest of the welfare of the school, and an Assistant Dean position created.

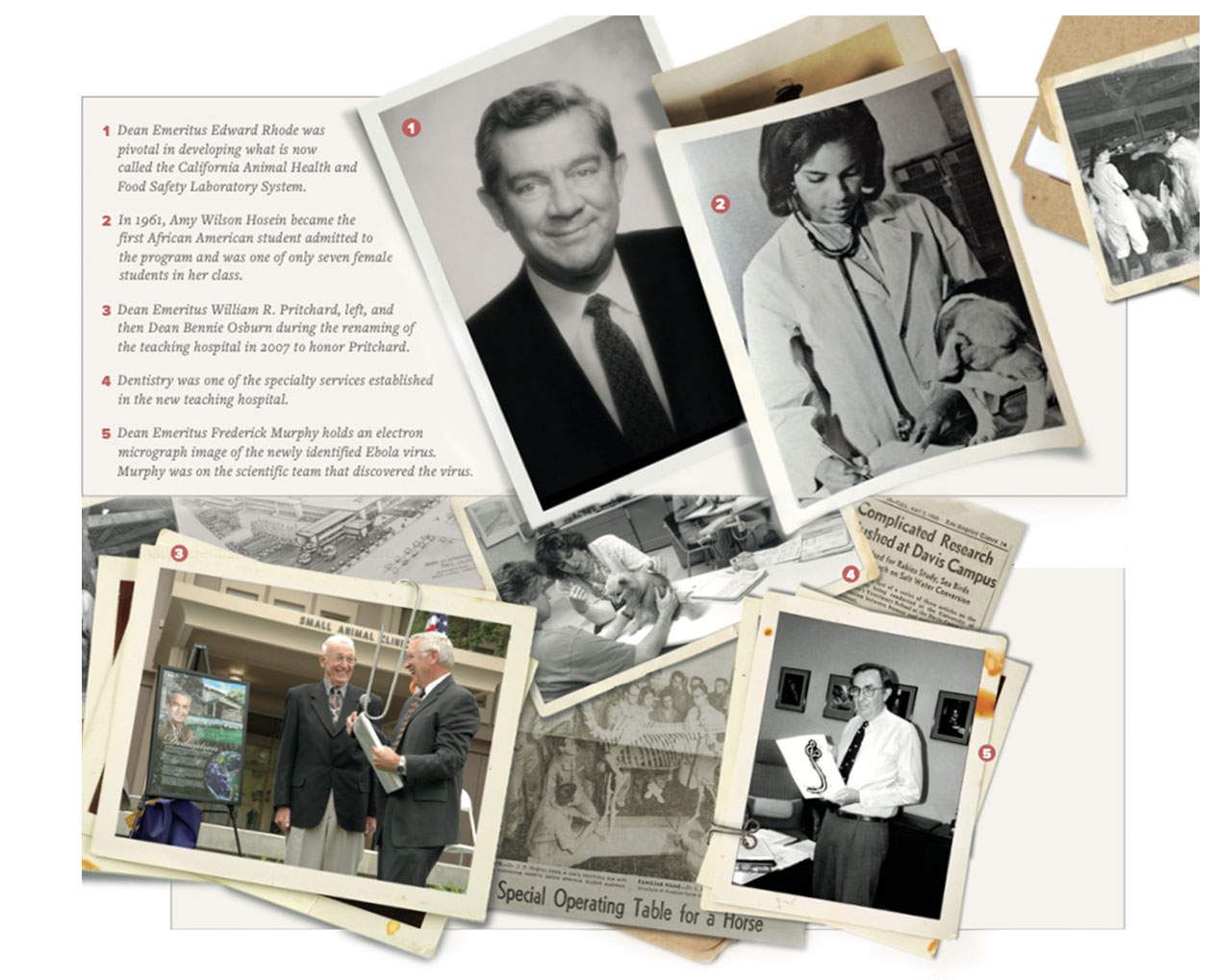

Founding faculty member Dr. Donald Jasper assumed the deanship in 1954 and served until 1962. An expert in Mycoplasma mastitis in dairy cattle, he had helped set the stage for future successes with his research focused on milk quality, mastitis screening and mechanisms to prevent udder injuries. By the end of his term, the school had achieved full accreditation from the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) Council on Education. It had also admitted the first African American student in 1961, Amy Wilson Hosein, one of only seven female students in her class.

Change Is A Comin’

By 1962 when Dr. William Roy Pritchard was appointed as dean, veterinary education across the country was going through a period of major change.

Prior to WWII, there were only 10 veterinary colleges in the U.S. and two in Canada. After the war, with veterans returning to colleges and universities, there was a massive influx of students in higher education institutions, many of them seeking a veterinary degree. With each college admitting only 50 to 60 students a year, there weren’t enough spots for highly qualified applicants. By 1962, eight more states, including California, had established veterinary schools or colleges, bring the total number to 20 in North America.

The curriculum of all schools was focused mainly on diseases and disease prevention of farm livestock with a growing concern for the health of dogs and cats. But clinical teaching was limited along with the facilities to do so.

There were few clinical specialists on faculty other than for medicine, surgery and reproduction. At the same time, research programs were growing as a result of a major expansion of the nation’s biomedical research effort, including the launch of the National Institutes of Health after WWII.

Pritchard noted in his memoirs that an accelerated rate of change was happening in the biomedical sciences, livestock production, veterinary practice and society as a whole in the 1960s.

“It was clear to me...that the school and the faculty would have to embrace unprecedented change and rapidly adjust school programs to newly forming realities,”

he wrote. “If the school hoped to serve these changing needs, we must welcome new ideas and new ways of doing things.”

Pritchard was also aware of the need to brand the school, bring more attention to its relatively obscure status, and educate the public on “how the school and its graduates served unique and vital needs of society and that most of what veterinarians do could not be done as effectively by any other group or profession.”

He gave dozens of talks to veterinary associations, livestock producer groups, and Rotary clubs. Excerpts from one of his talks, “One Medicine, a Concept Rapidly Becoming a Reality,” was published in the California Veterinarian in 1964, well before the current widespread popularity of the concept among veterinary medical leaders.

Over time, the phrase “One Medicine” was used interchangeably with “One Health.” Integration of veterinary and human medicine in a One Health approach began with the first comparative and preventive medicine department in a veterinary school at UC Davis. That concept expanded when the California National Primate Research Center (CNPRC), which had been established in 1962, moved under the auspices of the veterinary school in 1972. Scientists conducted federally-supported studies on nutrition and the effects of aging on cognition and memory; thalidomide and other agents that cause birth defects; and the effect of air pollution on primate lungs to establish and refine air quality standards.

Veterinary scientists at the CNPRC were also on the forefront of AIDS research and developing novel vaccines for HIV/ AIDS. While the CNPRC moved under the umbrella of the main campus’s Office of Research in 2009, veterinary faculty at the center continue to make groundbreaking discoveries, including those that have contributed to developing COVID-19 vaccines.

As large commercial livestock production became more common, producers expressed a greater need for veterinarians to monitor and prevent diseases intheir herds rather than seeking care for individual animals. That desire helped drive the establishment of the Master of Preventive Veterinary Medicine (MPVM)in 1967, the school’s second professional degree program. The curriculum, largely the brain child of Professor Calvin Schwabe, was modeled after the Master of Public Health degree and was the first course of its kind in any veterinary school.

Creation of the MPVM program was also a response to focus the DVM and graduate programs in ways that would better prepare UC Davis graduates for the many new job opportunities for veterinarians evolving in non-practice areas of the profession in both the public and private sectors. More than 1040 veterinarians holding MPVM degrees from UC Davis now serve in 51 countries around the globe. These graduates have helped expand the school’s international horizons to enhance animal health and food production, especially in underdeveloped regions.

While the need for veterinarians in society as a whole had become better understood, there was still a lack of governmental support and funding to expand training of future DVMs. Pritchard’s law degree proved useful when he spoke before the U.S. House of Representatives in 1966 regarding the future of veterinary education. His testimony helped garner federal funding for nine more veterinary schools across the country and to build veterinary teaching hospitals—including the one at UC Davis that carries his name.

In just over a decade, Haring Hall was too small for ongoing programs and didn’t include proper space for research, a clinical program or hospital space. That was finally rectified when the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital opened in 1970, on what was becoming the new campus for the school. Pritchard had been instrumental in its design, funding and implementation. The school named the hospital after him in 2007, making his name synonymous with the world-class veterinary program he helped create.

As the first of its kind, the hospital became the model for nearly every veterinary college in North America. For the first time, DVM students were able to select an area of species emphasis before graduation. That move set a new standard for expanded clinical training and the opportunity to specialize led to the more than 30 residency training programs now available at Davis—the largest residency program in the nation. Many of those specialties were pioneered at UC Davis,

including zoological medicine, neurology, behavior, shelter medicine and many others. The program annually trains 133 house officers in 39 specialty disciplines.

Toward the end of Pritchard’s tenure in 1980, the school was named #1 in the nation by U.S. News and World Report. The school also established a development program to provide current-use funds and build endowments for scholarships and other programs.

Protecting Public Health

During Dean Edward Rhode’s tenure from 1982–91, the school—in cooperation with the California Department of Food and Agriculture—established the California Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory System, later renamed the California Animal Health and Food Safety Laboratory System (CAHFS). The lab facilities in Davis, Turlock, Tulare and San Bernadino protect the state’s food supply, racehorse welfare, and other aspects of animal and human health.

Current biosecurity strategies to prevent disease outbreaks in production animal herds and flocks are based on early programs developed by school faculty and staff. For example, a UC Davis team worked with a USDA task force in 2002–03 to help stop the spread of exotic Newcastle disease from backyard poultry to commercial flocks. The collaborative effort contained the outbreak two years sooner than expected, and saved poultry producers more than $500 million.

The greater focus on herd health was also part of the impetus to create the Veterinary Medicine Teaching and Research Center (VMTRC) in Tulare—the heart of the world’s dairy production. Established in 1983, it is now renowned for its dairy cattle research and training programs. Among other breakthroughs, research conducted through the VMTRC led to the J-5 mastitis vaccine in 1988, improving animal health and saving dairy producers millions of dollars each year. Research, extension and diagnostic laboratory faculty have also helped producers manage Salmonella, E. coli and Neospora.

Another major shift was happening in the school’s student body. While more women had applied and been accepted into veterinary school beginning in the 1960s, by 1985, women DVM graduates outnumbered men for the first time at UC Davis. According to the AVMA, in 2022, women represented 83% of DVM graduates nationwide.

While state and federal support for veterinary education rose and fell throughout the years, Dr. Frederick A. Murphy—a preeminent veterinary virologist—became the sixth dean in 1991 at one of the most difficult times in the school’s history. In the first two years of his appointment, the school lost $2.5 million in state appropriations, dropped its entering class size from 122 to 108, and lost 15 faculty positions. Additional retirements during these years reduced the size of the faculty by more than 25 percent.

Under Murphy’s guidance, the school consolidated from 11 to six departments, streamlined administrative processes, increased opportunities for faculty collaboration and saved $300,000 annually without any staff layoffs. He also helped secure several private gifts to the school, including $1.6 million from the Lucille P. Markey Charitable Trust for a Center for Comparative Medicine; the $650,000 John P. Hughes Chair in Equine Reproduction, the school’s first endowed chair; and the $400,000 Koret Foundation endowment to initiate a faculty/student exchange program with the Koret School of Veterinary Medicine at the Hebrew University in Israel. Bequests to the school also jumped substantially.

To maintain and enhance the school’s research enterprises, a number of species or discipline focused centers were established similar to what is now known as the Center for Equine Health. These multidisciplinary centers provided a focal point for faculty collaboration and enhanced fundraising and grant writing success. Examples of centers founded during this time include: the Center for Companion Animal Health, the Wildlife Health Center, the Center for Comparative Medicine, the Veterinary Orthopedic Research Laboratory, and the Center for Vector-borne Diseases.

By 1996, the school’s research budget had grown to more than $46 million, a significant portion of it from private funding. When Murphy retired, he noted, “This is the best vet school in the world with only one problem: its aging facilities.”

Entering a New Millenium

Dr. Bennie Osburn accepted the role of dean in 1996, shortly before the school’s bicentennial celebration, and proceeded as a guiding force for new centers and programs throughout three terms. As an authority on the pathogenesis of viral diseases, Osburn was (and remains) strongly committed to research, food animal safety, and enthusiasm for the broad role of veterinary medicine.

The devastating floods of 1996 in Northern California highlighted the critical need to incorporate organized animal rescue methods into emergency response planning. Faculty members, staff and volunteer students worked with statewide agencies to build the Veterinary Emergency Response Team, a veterinary disaster response program based on the Standardized Emergency Management System.

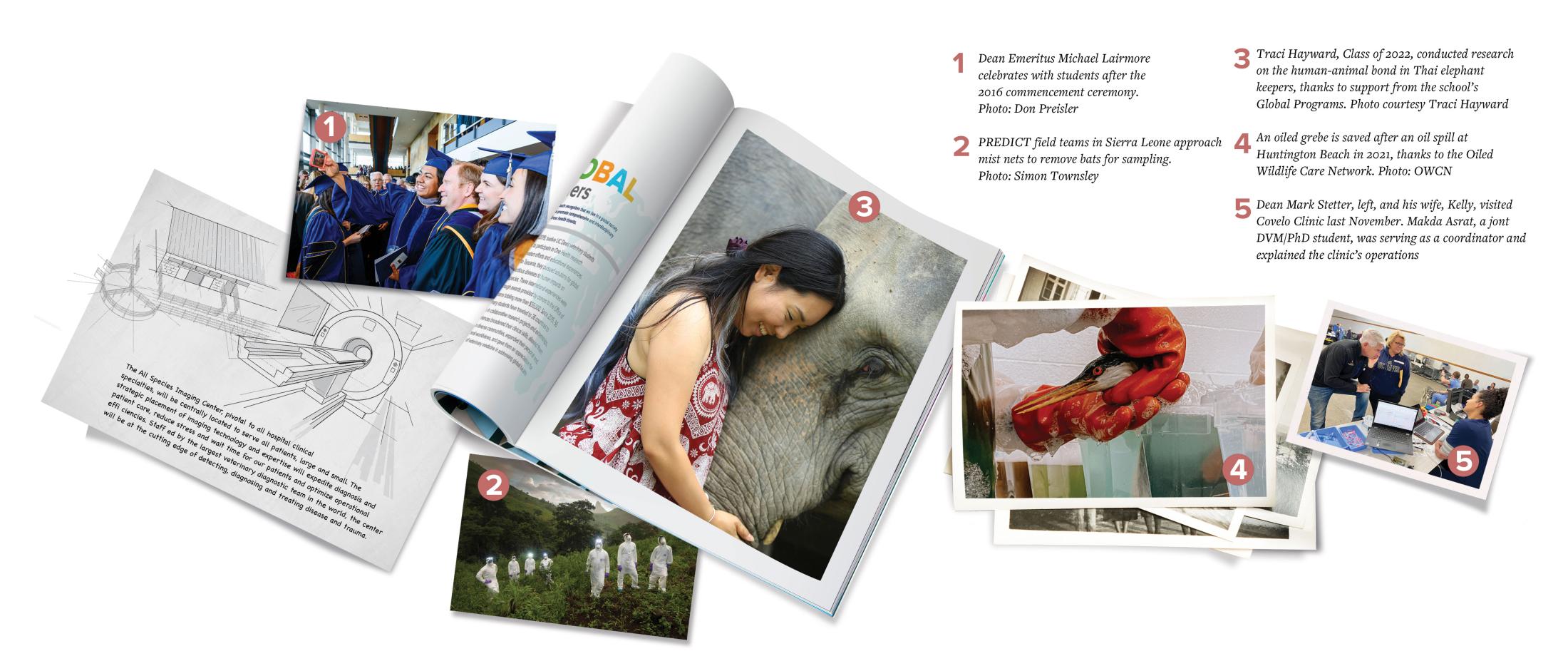

In another move that exemplified the school’s commitment to public service, the school signed a memorandum of understanding with what was then called the California Department of Fish and Game to establish the Oiled Wildlife Care Network. The statewide coalition of agencies, academic institutions and wildlife organizations housed under the school’s One Health Institute has become an international model for rehabilitation, research and education.

In 1998, while the school celebrated its 50th Anniversary, it also faced great challenges. The AVMA Council on Education placed the school on limited accreditation status for major facility deficiencies associated with the outdated Haring Hall. This touched off a massive $354 million long-range facilities plan that would last for the next decade, and include the construction of several state-of-the-art teaching, research and clinical facilities to transform the medical sciences complex into a modern veterinary campus.

The school also launched a $50 million campaign, the school’s most ambitious development fundraising effort to date. The money would be used to finance critically needed clinical and research space for the school’s Center for Companion Animal Health, as well as endowments for student scholarships, faculty positions and research centers. The Wayne and Gladys Valley Foundation provided $10.7 million— the largest gift in campus history at the time. The school was also able to garner additional funding ($2.5 million) from the state to grow its class size to 131, expand the resident program to 90, and create a presence in southern California through the University of California Veterinary Medical Center-San Diego.

Despite growing pains and challenges at the school’s mid-century mark, Osburn remarked, “This is the veterinary medicine that will lead us into a new millennium.” And it has.

Supporting Student Success

Dr. Michael Lairmore was recruited as dean in 2011 and proved an apt fit with combined training as a dairy and small animal veterinarian, and scientific research experience in retroviruses at the Centers for Disease Control. His background in a One Health approach helped lead the school’s efforts in pandemic preparation/prevention.

A couple of years before Lairmore came on board, USAID had granted $75 million to the Wildlife Health Center to support PREDICT—a program of global disease surveillance to prevent wildlife pathogens from spreading to humans, especially in disease “hot spots.” The consortium quickly produced a web-based, open-access map to help governments and health agencies track emerging infectious diseases around the world. That foundational work to better understand zoonotic pathogens— diseases that pass between animals and humans—proved critical in responding to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Under Lairmore’s guidance, the school earned two reaccreditations by the AVMA’s Council of Education, expanded faculty, and created new leadership and development opportunities, building the school’s academic and administrative foundation.

The school began responding more to social issues that were affecting students and the profession: student debt, mental health, racial disparities, and clinical education workload. That focus on students resulted in increased donor-funded scholarships to lower student debt; the creation of the Career, Leadership and Wellness Center; new business and financial management courses; and expanded mental health resources co-located within the veterinary school’s campus.

Lairmore also realized that the school needed fresh approaches to increase diversity, equity and inclusion. Thanks to many faculty, staff, student groups and campus leadership, the school has become one of the top three national veterinary schools for student diversity, while creating a community-wide effort to promote social justice.

In 2017, Lairmore worked with Chancellor Gary May and the school’s donors to launch a $500 million Veterinary Medical Center campaign to expand the existing veterinary hospital and continue providing state-of-the-art care. The campaign has built and opened the first facilities, and is moving forward with construction of a new All-Species Imaging Center.

The success of the One Health Institute inspired the creation of the Office of Global Programs, which has expanded educational and research opportunities for students and faculty worldwide.

The school also engaged in numerous partnerships, including the unique comparative oncology program within the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Under Lairmore’s leadership, the school reached new heights in global recognition, including top placements in U.S. News & World Report and QS World University Rankings.

Leading Veterinary Medicine into a New Era

Wildlife veterinarian Dr. Mark Stetter accepted leadership of the school in 2021 as its ninth dean. Stetter brings a fresh approach from his experience as director of animal operations for Walt Disney World for 15 years before his 10-year tenure as dean at Colorado State University. He says the international reputation of UC Davis as a leader in One Health was a primary attraction for him.

In his first year, Stetter embarked on a listening tour, bringing together constituent groups from around the school to discover the community’s greatest needs to foster an environment “where people feel empowered to do their best, and are excited and proud about what they do—a place where workplace culture and climate support diversity, equity, and inclusion.”

Stetter and the school’s Academic Council have determined four key priorities for the school to push forward immediately:

- Research: Determine ways to enhance the school’s research portfolio, break down bureaucratic obstacles and incentivize new trans/multi-disciplinary collaborations.

- Diversity, Equity and Inclusion: Establish outreach programs that will support a greater presence and inclusion of underrepresented groups in our faculty, staff, and student ranks while developing deeper connections with other DEI efforts on campus and across the profession. (Meet Monae Roberts, the school’s first Chief Diversity officer.)

- People First: Build a culture and climate at the school that will increase employee satisfaction and employee engagement.

- Facility Master Planning: Update our facility master plan for both short-term and long-term needs.

Despite the ongoing challenges presented by the COVID-19 pandemic, the school celebrated new records in research and philanthropic funding for the 2021–22 fiscal year, with $89 million received for research and $61.7 million from generous donors.

In addition, the school’s scholarship endowment surpassed $100 million— an important milestone for the long-term support of veterinary education.

As of 2022, UC Davis has graduated more than 7,000 doctors of veterinary medicine, is ranked #1 among the nation’s 32 accredited veterinary schools, and has the largest veterinary research program, as well as the largest and most diverse residency program worldwide.

In the prescient words of a prune farmer 75 years ago, UC Davis has become recognized as the leading institution of its kind in the world. The ingenuity and dedication of the individuals who built the foundation of this school continues to be reflected in our research facilities, classrooms, clinics and beyond—making a difference for animals, people and our planet.

Editor’s note: Much of the historical information for this article was provided by Dean Pritchard’s book “Memoirs of the Luckiest Man in the World,” Dean Jasper’s booklet “A Short History of the School of Veterinary Medicine,” and Dean Osburn’s “Reflections on the Past” published online. By no means is this article a comprehensive exploration of 75 years. Readers can dive deeper and view a historical timeline. If you would like to contribute an addition to the historical record, please email tjwood@ucdavis.edu.

Visit the 75th Anniversary website for more!

*University Archives Photographs, Dept. of Special Collections, General Library, University of California, Davis.