A New Era of One Health

A New Era of One Health

With the recent coronavirus pandemic, veterinary medicine has gained increasing recognition for contributing to human and environmental health. UC Davis is leading the way.

While the COVID-19 pandemic provides a prime example of why a One Health approach is critical to protecting the well-being of people, animals and their shared environment, UC Davis veterinary clinicians and researchers have many successful examples of collaborating with their colleagues in human medicine, biology and engineering to achieve breakthroughs. UC Davis’ highly ranked programs and comprehensive academic profile make it one of the few universities uniquely positioned to lead in One Health.

Disease treatments

Disease treatments

UC Davis has developed advanced treatment for cancer, spina bifida, epilepsy and other diseases in our pets, using clinical trials and collaborations among human and veterinary health professionals.

Medical technology

Medical technology

UC Davis pioneered the Mini Explorer II, the first comprehensive PET/CT imaging machine for companion animals, which served as a prototype for full human-size PET scanner created at the School of Medicine.

Disease surveillance

Disease surveillance

UC Davis has devised non-invasive disease surveillance techniques for pathogens that could jump from monkeys to humans.

Holistic habitat solutions

Holistic habitat solutions

UC Davis has conducted environmental studies at the wildlife/human interface to better guide protections for endangered species such as orcas and mountain gorillas.

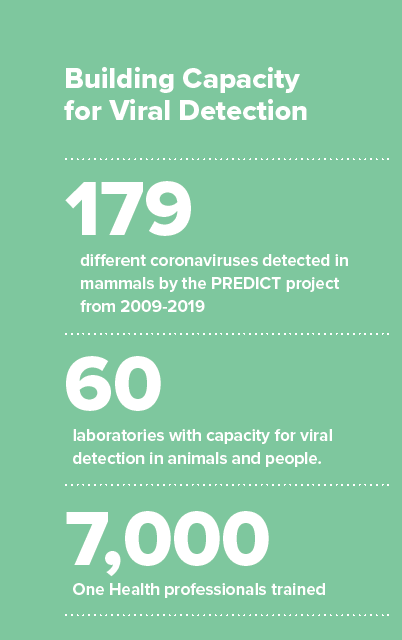

179

different coronaviruses detected in mammals by the PREDICT project from 2009-2019

60

laboratories with capacity for viral detection in animals and people

7,000

One Health professionals trained

In mid-January, Professor Christine Kreuder Johnson happened to be visiting colleagues at the Center for Molecular Dynamics in Nepal when they received a sample to be tested from a sick student.

“When that test came back positive for COVID-19, we knew it would spread,” Johnson said. “That individual had been hospitalized in Katmandu and later released; there was no way he hadn’t infected others.”

Johnson found herself at ground zero for witnessing the first cases in Nepal during the initial stages of the global outbreak of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus that causes COVID-19. After 10 years of serving as a co-principal investigator for PREDICT—a project of the U.S. Agency for International Development’s Emerging Pandemic Threats program—Johnson and her colleagues had anticipated a scenario like this.

“This spread of a virus that spilled over from animal hosts to humans is exactly what we had predicted,” she said. “To watch this pandemic develop reinforces everything I understand about epidemics, epidemiology and high-risk activities with wildlife. It’s tragic to see it unfold the way it has.”

"As COVID-19 spreads across the globe, it becomes clearer how infectious diseases are linked to environmental change."

One Health for All

While the concept of One Health has been tightly embraced by veterinary medicine, the public health sector has been slower to grasp the interconnections between animals, humans and their shared environment.

The idea has been around for centuries, documented as far back as 400 BC in Hippocrates' “On Airs, Waters, and Places.” In more recent times, the late Dr. Calvin Schwabe — a founding faculty member of the UC Davis School of Medicine as well as an epidemiology professor at the School of Veterinary Medicine — coined the term "One Medicine" in 1964 in his book, Veterinary Medicine and Human Health. Wildlife veterinarian Dr. William Karesh pioneered preventive health programs for wildlife species and coined the term “One Health” in 2003. He serves as consortium partner in the PREDICT project.

The approach gained prominence when the Centers for Disease Control established its One Health Office in 2009. In the same year, the UC Davis One Health Institute formed and became home to the PREDICT project, funded by $200 million in USAID grants to strengthen global health security through early detection of potentially pandemic zoonotic viruses, or pathogens that can move between animals and people.

The PREDICT project has been active in more than 30 countries throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America

The PREDICT project has been active in more than 30 countries throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America, working in areas where contact between people and animals is high, suggesting spillover risk is greatest. They have built capacity for viral detection in animals and people in more than 60 laboratories and trained a One Health workforce of nearly 7,000 One Health professionals to think globally while acting locally.

In the past decade, the PREDICT project detected 179 coronaviruses in mammals, of which 113 were new. A few of those newly identified coronaviruses have been related to viruses that have caused spillover events to humans, such as Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) related viruses.

Previously scheduled to conclude in March 2020, PREDICT received a six-month, $3 million extension to provide emergency support to collaborating countries in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. The project will continue to provide technical expertise to support detection of SARS-CoV-2 in Africa, Asia and the Middle East, as well as to investigate the potential animal source or sources of the virus using data and samples collected over the past 10 years in Asia and Southeast Asia.

In addition, UC Davis and its consortium partners have received up to $85 million in USAID funding over the next five years to implement the One Health Workforce program—Next Generation project. The project is working to develop sustainable training programs at universities to train the next generation of One Health professionals in Central/East Africa and Southeast Asia to address complex health threats, including antimicrobial resistance and zoonotic disease.

Environmental Impacts on One Health

As COVID-19 spreads across the globe, Johnson says it becomes clearer how infectious diseases are linked to environmental change. In a timely study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B in April, Johnson and her colleagues showed that wildlife exploitation by humans through hunting and trade, as well as habitat degradation and urbanization, facilitates close contact between wildlife and humans, increasing the risk of virus spillover. Many of these same activities also drive wildlife population declines and the risk of extinction.

“Spillover of viruses from animals is a direct result of our actions involving wildlife and their habitat,” Johnson said. “The consequence is they’re sharing their viruses with us. These actions simultaneously threaten species survival and increase the risk of spillover. In an unfortunate convergence of many factors, this brings about the kind of tragedy we have now.”

Dramatic alterations in our global climate also drive how viruses move among species and regions. A 15-year study led by Professor Tracey Goldstein, published recently in the journal Scientific Reports, linked melting Arctic sea ice to the emergence of phocine distemper virus, or PDV, that could threaten Northern Pacific marine mammals.

PDV was responsible for killing thousands of European harbor seals in the North Atlantic in 1988 and 2002, and was first identified in the Pacific in northern sea otters in Alaska in 2004, raising questions about when and how the virus reached them. The research highlighted how the radical reshaping of historic sea ice may have opened pathways for contact between Arctic and sub-Arctic seals that was previously impossible, allowing for the virus’ introduction into the Northern Pacific Ocean.

“The loss of sea ice is leading marine wildlife to seek and forage in new habitats and removing that physical barrier, allowing for new pathways for them to move,” said Goldstein, an associate director of the One Health Institute. “As animals move and come in contact with other species, they carry opportunities to introduce and transmit new infectious disease, with potentially devastating impacts.”

Tackling Pandemics Through a One Health Lens

While the leadership of UC Davis in protecting global health has garnered international attention in headlines across the world, the recent COVID-19 pandemic serves as a real-time example of how critical a One Health approach is to saving lives. As the outbreak moved from a global health emergency to a full-blown pandemic—and the PREDICT and One Health Workforce affiliates mobilized in the field and laboratories in Africa and Asia—UC Davis clinical pathologists, infectious disease physicians and scientists collaborated to launch a coronavirus research program.

This team came together quickly thanks to existing strong partnerships among human and veterinary health professionals at UC Davis. They are working to unravel the biology and infectious pathology of SARS-CoV-2, and to develop means for prevention and ultimately treatment. They began by isolating, characterizing and culturing this new coronavirus from a patient treated at UC Davis Health—the first community-acquired case in the U.S.—with the goal of better understanding the effects of the virus.

While the leadership of UC Davis in protecting global health has garnered international attention in headlines across the world, the recent COVID-19 pandemic serves as a real-time example of how critical a One Health approach is to saving lives.

Reagents developed and knowledge gained will make use of UC Davis’ existing infrastructure, including for high-capacity clinical laboratory testing. Widespread testing is crucial to unravel the true prevalence, lethality and contagiousness of COVID-19. Culturing the virus in the laboratory will allow researchers to investigate the basic biology of coronavirus — how it attacks and invades cells, and what treatments might work against it.

Genetic differences between the coronavirus isolates in California and those from other countries or parts of the U.S. may give clues about how the virus was introduced and is spreading. Dr. Bart Weimer, professor of population health and reproduction at the veterinary school, is working to establish if genomic variation in the virus is predictive of changes in infection rates. Monitoring differences in virus genomes may help public health authorities target areas about to experience an upsurge in infections. His lab is currently investigating mutations that might make the virus more susceptible to jumping to species other than humans.

Tracking COVID-19 cases and testing at the county, state and national level is also critical to responding to the pandemic. Dr. Christopher Barker, an associate professor of epidemiology at the veterinary school, led a team in developing a new web application featuring interactive maps and graphs. The COVID-19 U.S. map allows users to hover over states or click on a specific state to find information on cases, testing, deaths and other COVID-19 information over time. The website uses open, publicly available data from the COVID Tracking Project, Johns Hopkins University and the New York Times.

The school is actively pursuing additional opportunities to help respond to the pandemic. UC Davis has made funding available through small grants for SARS-CoV-2 related work, and faculty and staff are also pursuing state and federal funds.

“We have some of the top experts in the world at the school, and we’re doing everything we can to get them fully mobilized,” said Dean Michael Lairmore. His career pivoted in the 1980s when his work on ovine lentiviruses intersected with another zoonotic epidemic: AIDS. “We know from experience that this won’t be the last instance of this type of virus we encounter—and each time it happens, veterinarians become more integral to the solutions.”

Broad Perspective Key to One Health

While COVID-19 has devastated parts of the world, causing tremendous human suffering and economic upheaval, Goldstein credits the foundational work done by PREDICT over the past decade as instrumental in helping countries have the capacity to respond to the current crisis.

While COVID-19 has devastated parts of the world, causing tremendous human suffering and economic upheaval, Goldstein credits the foundational work done by PREDICT over the past decade as instrumental in helping countries have the capacity to respond to the current crisis.

“Many of the labs that we were fortunate to be able to work with had protocols in place to detect the virus before a sequence or specific test became available,” said Goldstein, who also serves as pathogen detection lead for the PREDICT project. “We have colleagues in Nepal, Thailand and Cambodia who were all able to detect the new coronavirus in their countries because of the work that PREDICT had done previously. They are trusted resources in their countries, assisting with coronavirus detection and included on government task forces to support the response.”

While PREDICT has been granted a brief extension, Johnson emphasized that it’s clearer than ever that this virus surveillance work needs to continue.

“The threat is always there,” she said. “Maintaining capacity and networks of scientists that are engaged and supported in a One Health approach is essential for us to have any kind of reliable global health security.”

Goldstein added that PREDICT has shown that these viruses and their animal hosts are much more widely distributed that previously thought.

“We need to think more broadly than we have before for the benefit of public health.”