Discoveries

Discoveries

Mountain Gorilla Populations on the Rise

Mountain Gorilla Populations on the Rise

Mountain gorillas are the only great ape in the wild whose numbers are increasing, thanks in large part to the efforts of Gorilla Doctors, a partnership between the Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project, Inc., and the Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center at UC Davis. The organization is credited for half of the annual population growth rate of human-habituated mountain gorillas (those accustomed to the close proximity of people to facilitate research and tourism). Census surveys place their current world population at 1,063. While the increased numbers represent a victory, the total population is still small, and mountain gorillas continue to face ongoing risks such as habitat encroachment, disease transmission, and poaching.

Toxoplasma Hijacks Cells to Reach the Brain

Toxoplasma Hijacks Cells to Reach the Brain

A tiny single-celled organism, Toxoplasma gondii, can cause big problems. This common parasite can infect all warm-blooded animals, often without symptoms. But it can also cause serious complications by hijacking immune cells to spread from the site of infection to other organs in infants born to mothers infected during pregnancy and those with weakened immune systems. A UC Davis team led by Jeroen Saeij identified a gene that disguises the parasite in the body, allowing it to spread to distant organs. As described in their Cell Host and Microbe paper, the researchers knocked out this gene in the parasite and infected mice with the modified organism. The deletion significantly inhibited the parasite’s ability to reach distant locations in the body, such as the brain. This discovery could be the first step in developing novel treatments against Toxoplasma infection.

Gut Health Critical to Treating HIV and SIV infections

Gut Health Critical to Treating HIV and SIV infections

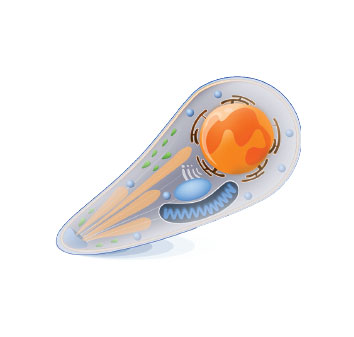

Bacteria may be the key to restoring gut damage caused by viruses such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Inflamed gut lining (leaky gut) is due to loss of a protein responsible for regulating cell metabolism, which in turn damages the mitochondria, a cell’s powerhouse. UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine and School of Medicine DVM/Ph.D. student Katti Horng Crakes served as first author on a PNAS study that found that Lactobacillus plantarum bacteria rapidly repaired leaky gut in monkeys infected with chronic simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) by restoring the mitochondria in the gut lining. These findings provide translational insights into restoring gut immunity and function, both of which are essential for successfully treating HIV.

Detection Dogs on the Trail of Endangered Lizards

Detection Dogs on the Trail of Endangered Lizards

Conservation dogs help monitor endangered mammal populations - from bears to whales - and now reptiles. Canines are trained to identify the scents of endangered animals and their droppings, or scat. Researchers extract DNA from the scat to identify where these species live and how many of them are in a specific area. UC Davis researchers, led by Mark Statham of the Mammalian Ecology and Conservation Unit, used dogs to sniff out the presence of endangered blunt-nosed leopard lizards in California’s San Joaquin Valley. Results from the four-year survey (published in the Journal of Wildlife Management) can help scientists determine if current conservation efforts are working and help refine the approach for larger scale application.

Melting Sea Ice Linked to Virus Spread

Melting Sea Ice Linked to Virus Spread

Melting Arctic sea ice is causing the rapid spread of a deadly virus in marine mammals. Tracey Goldstein, associate director at the school’s One Health Institute, led the 15-year study published in Scientific Reports, which revealed that peaks of phocine distemper virus exposure and infection in seals, sea lions, and sea otters coincide with melting trends in Arctic sea ice. Once animals are exposed, they have the capacity to carry the virus long distances through pathways previously blocked by sea ice, with potentially devastating impacts. As human-driven climate change continues to reshape sea ice, the spread of pathogens could become more common and affect more species.

Genetics Impact Canine Coat Color

Genetics Impact Canine Coat Color

Some dogs exhibit more intense coat colors because they have more copies of certain regions of DNA. Dr. Danika Bannasch led a UC Davis team that investigated the range of red coat color in Nova Scotia Duck Tolling Retrievers. In their Genes paper, they identified a region of DNA that can be present in multiple copies and influences a gene known to be related to hair color. In some breeds, dogs with a higher number of copies had more intense coat colors. The number of copies affects coat color intensity through the distribution of pigment along the length of the hair. Further work is needed to explain variation in coat color intensity in some breeds such as Golden and Labrador Retrievers.